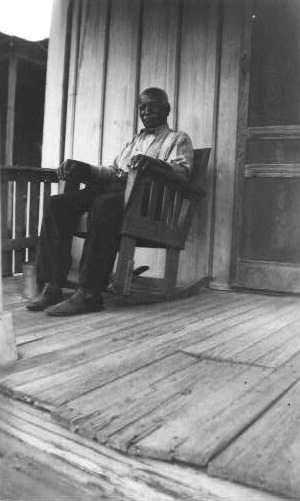

James H. Martin

James Martin, San Antonio, Texas, May 30, 1937.

Alfred E. Menn, photographer. Library of Congress.

James H. Martin was born in 1847 in Alexandria, Virginia. His father was apparently a free black, Preston Martin, born in Virginia circa 1808. His mother was Lizzie Martin, possibly née Elizabeth Burks. James Martin joined the U.S. Army by the end of the Civil War and then became a Buffalo soldier. He was interviewed in 1937 at his place of residence, 311 Dawson Street, San Antonio, Texas, by Alfred E. Menn, a WPA employee. He was then 90 years old and described as "active… slender, wiry… [with a] full set of his own teeth." He died nine years later and was buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

The following oral account is from the Work Projects Administration [orig. Works Progress Administration], Federal Writers Project, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.

"I was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1847. My father was Preston Martin. My mother was Lizzie Martin. My mother was a slave. My grandfather was one of the early settlers of Virginia. He was born in Jamaica and his master took him to England. When the English left England to come to Virginia, they brought the colored people along as servants but when they got here, everybody else had slaves and the colored people from England became slaves. My mother was born in the West Indies.

"A man named Martin brought my grandfather from England. We took his name. And when the master was nearly ready to die he made a will and in it he said the youngest child in the slaves must be made free. The youngest child was my father and he was set free, when he was sixteen years old. That left me and my brothers and sisters free and all the rest of the family was slaves.

"My mother was born a slave. Her master had a big plantation near Alexandria. His daughter was Miss Liza. She was the same age as my mother. When Miss Liza came home from school, she read her lessons to my mother and so my mother got the same education as her mistress. They were just about the same age.

"When my mother's master died he left my mother with other slaves to Miss Liza, cause the slaves was property just like horses and they paid taxes on them. And then my father liked my mother and told her they must get married. My mother liked him too and she said to Miss Liza, 'I'd like fine to marry Preston Martin.'

"Miss Liza says: 'You can't do that Lizzie 'cause he's a free nigger and your children would be free. You gotta marry one of the slaves on this plantation.' Then Miss Liza lined up ten or fifteen of the black slave men for my mother to pick from. My mother says she don't like any of the plantation men, she wants to marry my father. Miss Liza argues and my mother just acts stubborn. She wants to marry my father. Then Miss Liza says, 'I'll talk to the master.'

"The master thinks Miss Liza ain't picked out the right kind of man so he lines up another lot. But my mother she's just stubborn. She says she only wants to marry Preston Martin. Then the master says, 'I can't lose property like that. I can get more for you than $1,200 but if you can raise $1,200 you can buy yourself free.'

"All this time my mother and father is savin' money. They never tell me how much. Miss Liza often lets my mother earn a little money sewin' or sellin' milk or anything and she saves every penny. So one day they goes to the master and Miss Liza and they lays down $1,200 and they gets married. Master Tom don't like it but he's promised and can't back out.

"So me and my brothers and sisters is the only free ones in our family. It's a big family too. And often some of them is sold on the auction block. They're put in stalls like the pens they use for cattle, a man and his wife with a child on each arm. And there's a curtain, sometimes just a sheet over the front of the stall so the bidders can't see the 'stock' too soon. The overseer's standin' just outside with a big black snake whip and a pepper box pistol in his belt. Across the square a little piece there's a big platform with steps leadin' to it.

"Then they pulls up the curtain and the bidders is crowdin' around. Them in back can't see.

"So the overseer drives the slaves out to the platform. And he tells the ages of the slaves and what they can do. They have white gloves there. And one of the bidders takes a pair of gloves and rubs his fingers over a man's teeth. And he says to the overseer, 'You call this buck twenty years old. Why there's cups worn in his teeth. He's forty years old if he's a day.' So they knock this buck down for $1,000. 'Cause they calls the men bucks and the women wenches.

"When the slaves is on the platform what they calls the block, the overseer yells, 'Tom or Jason, show the bidders how you walk.' Then the slaves steps across the platform and the biddin' starts.

"Some of the masters has 400 or 500 slaves. And they votes 'em. What, you don't think they votes 'em. They pays taxes on 'em. How'd the South ever git them 'lectoreal votes? I 'member when Buckanen (Buchanan) was 'lected. The South thought he would help slavery. But he says he's agin' one piece of human flesh belongin' to another piece of human flesh.

"At these slave auctions the overseer yells, 'Say you bucks and wenches get in your hole. Come out yere. Then he makes 'em hop, he makes 'em trot. He makes 'em jump. 'How much,' he yells, 'for this buck? $1,000, $1,100, $1,200?' Then the bidders makes offers accordin' to size and build.

"When I'm old enough, I'm taught the trade of saddler. They gave me an education. When I'm seventeen or eighteen I enlist in the United States army. I was in the Ninth Cavalry under command of Captain Francis F. Dodge. We were sent to Texas where they had trouble with the Indians. I served for a time at Fort Sill, Fort Davis in West Texas, Fort Stockton and Fort Clark. I was in two battles with the Indians in the Guadalupe Mountains. I also served under Colonel Shafter in March, 1871. I got my discharge under General Merritt in 1872. Then I came to San Antonio. First I went back to Alexandria but everything had changed. So I came back here. I worked for a while at saddlery for Ramsey and Ford.

"I'll tell you something else you didn't know. I helped to bring the first railroad to San Antonio. The Southern Pacific in those days only ran to somewhere near Seguin. I was a spiker and worked the whole distance. Then I helped to build the old railroad from Indianola to Cuero to Corpus Christi. Cunningham and Schleister, I think were the contractors for the Southern Pacific. That was in 1873 and 1874.

"This road front of my house used to be the old Gonzalez road; 'twasn't much of a road. I've seen wagons bogged up to the hub right outside this door.

"You could go five miles from where you sit and run into big herds of buffalo. I drove cattle for several of the big outifts. We drove 2,000 to 3,000 head from South Texas sometimes clean up to Dakota. I drove for John Lytle, Brockhaus, Fant, Kieran and Bill Sutton.

"No sir, there wasn't any trails only what we made. We drove the cattle about two miles and then we'd let them graze. There wasn't any fences. Generally we headed toward West Texas and then crossed the Red River at Fort Dodge. Often we ran into herds of buffaloes and sometimes the cattle stampeded. The Indians didn't bother us much. They'd come into camp and ask for meat. We'd kill a steer or bull, they didn't care which and give them the meat. We knew if we didn't, they stampede the cattle.

"They say a rollin' stone gathers no moss, but I tell you if I wasn't so old I'd be rollin' right now. This is no place for colored people. That was what sent me to Alexandria when I was mustered out of the army. But everything was so changed I came back. I got a job in Ramsey and Ford's saddlery place but the sentiment was too strong against the colored people. The trouble with the people here is they don't know how to treat humanity, white or black. I know the sayin' when you're in Rome do as Rome do. But the Romans got the best of it.

"I get a pension from the government. I've been married twice. I'm separated from my second wife. She lives in town here, up in the Highlands.

"Right here where I'm sittin', I've seen wolves and coyotes sneakin' by. And just a little piece over there (pointing to a house 500 feet distant across the Southern Pacific tracks) was a kind of wallow where the deer and antelope used to come to drink.

"Yes sir, I'm bachin' it. This is where I entertain my visitors." (The room contained a bookcase, curtained, easy chairs and a desk. It was neat and clean. Next was the bedroom, also showing good attention. "And here's where I do my cookin'." The kitchen was large, held a wood stove and beside it a quantity of cord wood, neatly piled. "If I wasn't so old," he concluded, "I'd be traveling around again. I don't believe any man can be educated who ain't traveled some. I like better to travel a lot."

|

Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery |

|

April 29th, 2007